In 1922, artist Alice Lescinska Lowe Ferguson (1880-1951) and geologist Henry Gardiner Ferguson purchased a ramshackle and overgrown farm on the banks of the Potomac River in Maryland to use as a retreat from their Washington D.C. home.

At the farm, called Hard Bargain, they lived with a cast of characters out of a children’s book. There were cows Elizabeth and Jane, pigs Solomon and Fear Naught Matchless Lady, horses Prince and Bonnie Jean, and Pogie the bull, who liked to twirl a wheelbarrow on his head, then graduated to pushing farm vehicles down hills. Their dog, Caligula Sin Verguenza (“shameless Caligula”), lived up to his name, terrorizing many of the farm animals.

Local collectors had long known that arrowheads could be found in Hard Bargain’s fields. The Fergusons allowed them to continue to surface collect, and also picked up many artifacts themselves, so much that they eventually built a little shed to display all their finds.

“We thought it would be great fun to sit on a dump heap and watch somebody dig knowledge out of the ground,” but the professional archaeologists they tried to interest in their site were all busy working in more exotic, or at least far away, lands. One day, however, a “group of lads” snuck onto her land and dug a trench through her alfalfa field, absconding with their finds. On their way out, the teenagers used a rifle to take potshots at various mailboxes and other things that did not belong to them. The Fergusons (and their neighbors) were furious, but also intrigued. They and the “gang” (a mixed assortment of friends and acquaintances who came to the farm on weekends to drink, hang out, play volleyball, help with farm chores, and drink) began haphazardly digging for artifacts beneath the alfalfa.

“In those days I dug, too, but as time went on I spent more and more time sitting on the dump heaps, watching them burrow and getting a little morose about it all. The more they dug…the more convinced I was that the site was really important and not a proper plaything for anybody.”

In the decade or so since purchasing Hard Bargain, Alice Ferguson had continued to paint, designed and had built a new farmhouse and other farm buildings, oversaw the farm operations, and become an honorary firefighter in the village. Now, in her mid-fifties, she set out to learn how to be an archaeologist.

In the summer of 1935, six men were hired: three black men to remove the plow zone soils, and three white “intelligent lads of college age” to identify and excavate any features that were uncovered.

Over the next six years, Alice Ferguson supervised the excavation of what would become known as the Accokeek Site (18PR8). The size and scale of the excavation expanded greatly. Friends from the U.S. Geological Survey (where her husband worked) helped with laying out a grid and mapping the site. Additional diggers, many of them local high school boys, this time presumably without firearms, used shovels to remove the plowzone and reveal stockade lines, pits, and other features. These were excavated by hand and photographed. A series of ossuaries (burial pits where disarticulated human remains are reburied) containing the remains of almost 800 individuals were excavated, as were 39 dog burials. Over 150,000 artifacts were recovered, and the little log cabin museum on the farm expanded to five buildings.

As the finds piled up, many professional archaeologists and other scientists (several associated with the nearby Smithsonian) provided guidance or visited the site, including Aleš Hrdlička, T. Dale Stewart, William Ritchie, Donald Cadzow, Henry Bascom Collins, Jr., James Griffin, John Hack, and Charles O. Turbyfill.

The largest locus at Accokeek contained two separate prehistoric stockaded villages. While the older component dates to the Early-Middle Woodland period, Ferguson identified the more recent occupation as Moyaone (pronounced Moy-OWN), a Piscataway village that John Smith had visited in AD 1608. This occupation, however, contained no European artifacts and is now thought to date no later than about AD 1550, so is unlikely to be the historically known Moyaone.

The advent of World War II essentially brought an end to her archaeological fieldwork as she focused on actual farmwork. With the war’s end, Alice Ferguson looked to write up her report on Moyaone, but as her health deteriorated, she was unable to finish the necessary revisions. Alice Ferguson passed away in 1951.

Alice and Henry Fergusons’ “combination of wealth, social standing, generosity, sincerity, unconventionality, intelligence and glamour left a lasting impression” (Sams 2015) on their friends, colleagues, the rural Maryland landscape, and on Mid-Atlantic archaeology. Money from her will was used to create the Alice Ferguson Foundation and to fund a fellowship awarded to Robert L. Stephenson, who completed the artifact analysis (“counting and classifying innumerable strawberry boxes of uninspiring potsherds,” according to Charles McNutt [1995:77]), which was published in 1963 (Stephenson and Ferguson 1963).

Several new ceramic ware types defined from the site, including Mockley, Pope’s Creek, Accokeek, Potomac Creek, and Moyaone, were important in developing a ceramic chronology in the Mid Atlantic. The ceramic typology developed by Stephenson, although modified by more recent research, is still used today.

The Accokeek Site was later listed as a National Historical Landmark and part of Ferguson’s farm was donated to the National Park Service to form Piscataway National Park. The Park is across the Potomac River from George Washington’s home and serves to protect Mount Vernon’s viewshed from modern development. The Alice Ferguson Foundation and Hard Bargain Farm are still in existence.

Quotes from Alice Ferguson are taken from her 1941 memoir, Adventures in Southern Maryland.

References:

McNutt, Charles H.

1995 Robert L. Stephenson: The Plains Years. Plains Anthropologist 40(151):77-80.

Sams, Daniel

2015 Wagner House. Maryland Historical Trust, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form Inventory No. PG:83-32.

Stephenson, Robert L., and Alice L.L. Ferguson, with sections by Henry G. Ferguson

1963 The Accokeek Creek site; a middle Atlantic seaboard culture sequence. Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, No. 20.

Revised from a previous post.

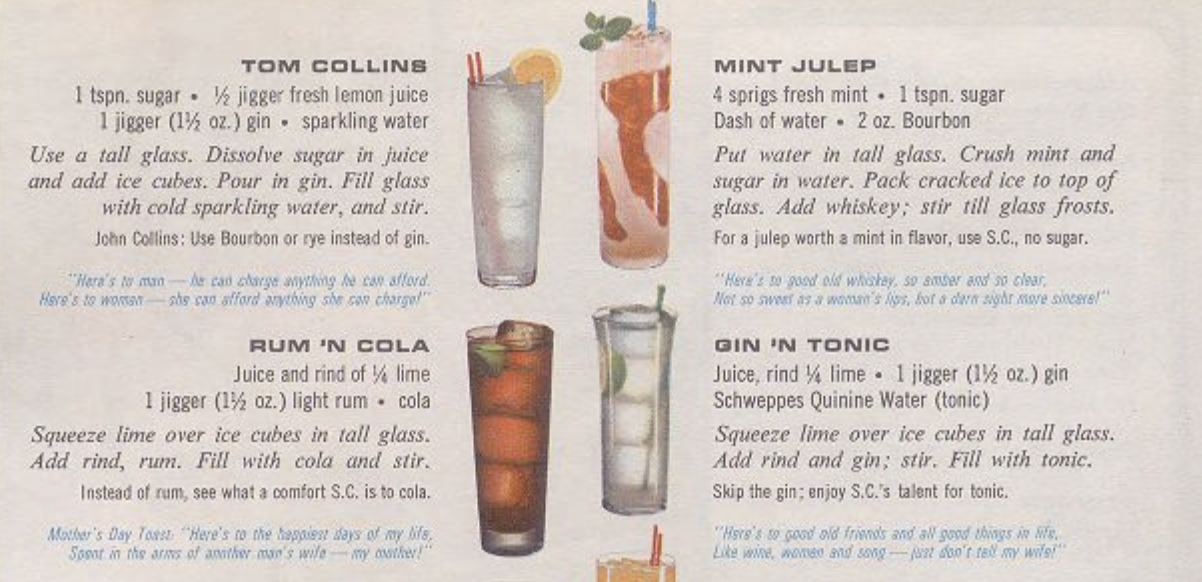

#cocktails #1960s

#cocktails #1960s